Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

When we teach Computer Science we often draw on other subjects, whether Maths (for example, to understand logical operators), English (if doing natural language processing), Ancient History (if using Roman mosaics as a way to introduce bit-mapped graphics), Psychology to understand human computer interaction or in my favourite case Conjuring (to teach just about any Computer Science!) Sometimes, students may already understand the topic from the other discipline, at other times you may be teaching that topic first and then building up on it.

How do you do that well? How do you use content from other subjects to effectively teach Computer Science topics? Autonomy tours are one way to think about this, and so reflect on and improve your lesson plans.

You may have heard of Semantic Waves as a way to improve lesson plans. Karl Maton’s idea of Autonomy tours come from his same underlying sociology theory, LCT. The idea of autonomy in a teaching context is to separate thinking about the content you are actually teaching from the purpose of teaching it.

Using conjuring to teach computing

Let’s take my use of conjuring to teach computer science to primary school children to illustrate. First, we need to be clear of what is the core aim of this teaching. In my case let us assume it is to teach computer science. Therefore, that is my target.However at any particular time in a lesson, I might be talking about computer science or I might be talking about conjuring. That is the lesson content at that point in the lesson. However, my purpose of doing that at a particular point could be about something else. I could, at that point, be talking about conjuring with the immediate aim of teaching the class a magic trick (so that later I can use the understanding gained to teach something else). I may want you to be able to do and understand the Invisible Palming card trick, for example. Alternatively, I could be talking about conjuring with the explicit aim of teaching computer science. For example, once you understand self-working tricks (which work, having a magical effect, as long as you follow the steps precisely and in the right order). Then I would be using conjuring for the purpose of teaching computer science.

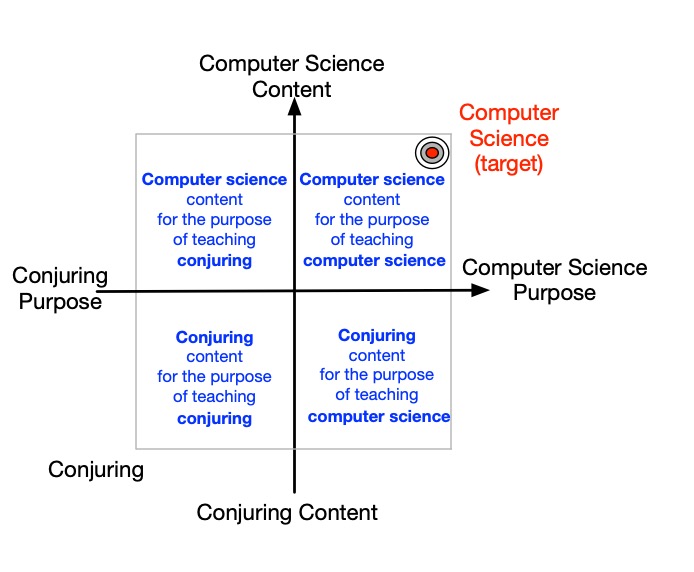

There are four possibilities overall:

- Teaching computer science content for the purpose of teaching computer science.

- Teaching computer science content for the purpose of teaching conjuring.

- Teaching conjuring content for the purpose of teaching computer science.

- Teaching conjuring content for the purpose of teaching conjuring.

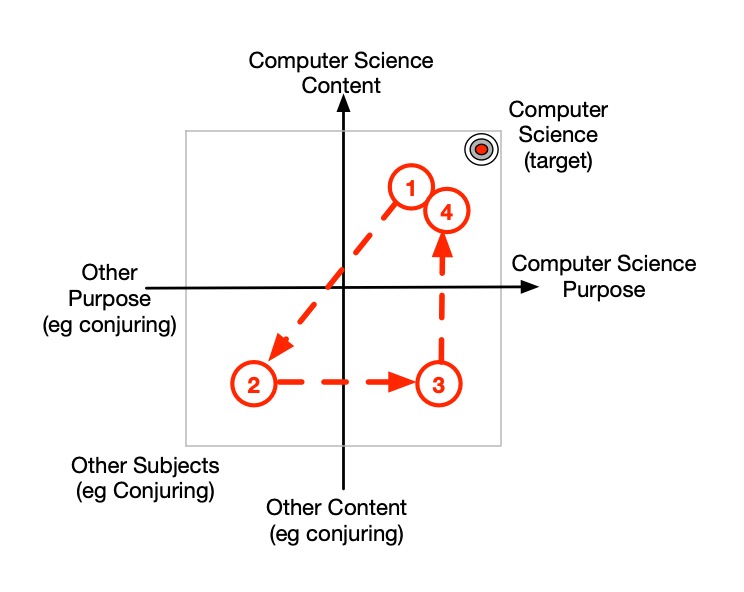

We can visualise all this on a diagram showing a plane consisting of the two dimensions of content and purpose as the axes (see Figure 1). This is the Autonomy plane. It visualises four quadrants corresponding to the above four possibilities.

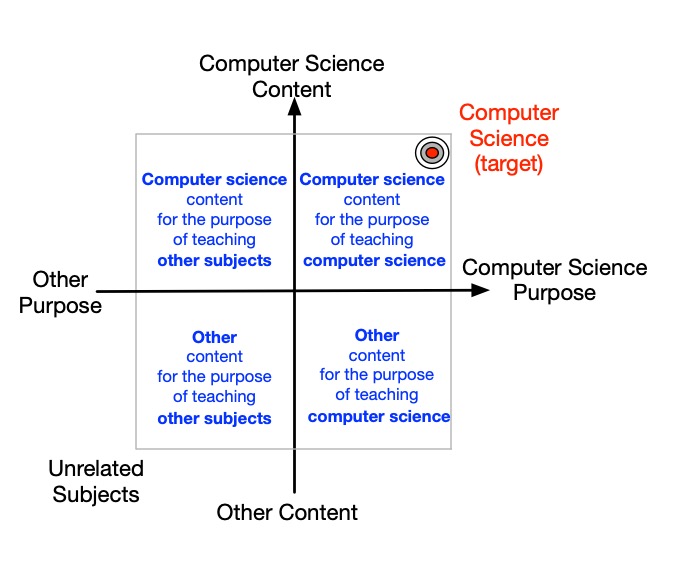

Strictly, when thinking about Autonomy, you do not have a pair of topics like this but have a target (like computer science) and everything else at the other end of the dimensions, rather than a specific thing like Conjuring. The further from the target content or purpose is, the further away from the top-right of the diagram it is. Autonomy considers a continuum not a binary choice.

To keep things simple we will only consider Conjuring, as though it were the only other subject involved. In reality, other subjects could be involved too such as covering some Cognitive Science or Maths to explain a magic trick. The plane could also then be divided more finely.

What use is the autonomy plane? It gives us a way to visualise how we use non-computer science content to help teach Computer Science (and vice versa) in a lesson plan. Alternatively, if observing a lesson, it can help us visualise the way that lesson actually takes place, given real lessons often are adapted to the situation as it happens.

A one-way trip

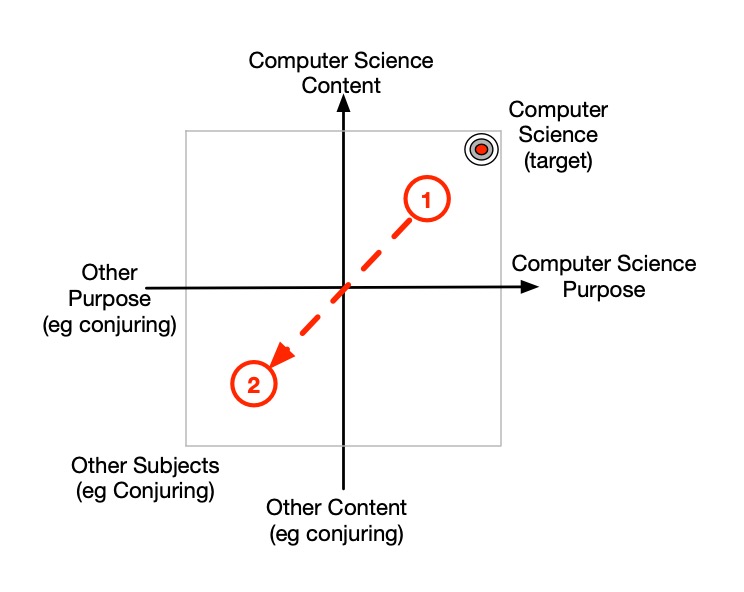

Looking at a lesson plan, we can plot how the lesson progresses on the autonomy plane. For example, suppose we explain the Computer Science topic of what an algorithm is and then do a magic trick, with the overall idea that it will illustrate how a trick is following an algorithm. However, suppose we focus on the trick and how it works to make sure the students can do it. The outline plan is:

- Explain what an algorithm is

- Teach and have the students do the Invisible Palming trick

This is perhaps more likely to be how it pans out due to say lack of time, rather than what we planned it! Plotting this on the autonomy plane we get the picture of Figure 3.This is a one-way trip from top-right to bottom-left. In general such one way trips do not solidly teach the target. First of all, the lesson takes us away from the target. There is also no real linkage of the conjuring to the target of Computer Science. Overall our purpose may have been that it would help teach Computer Science, but when we actually do the step we are focussed on teaching the trick so the class know the trick with the intension of building on that.

A return trip

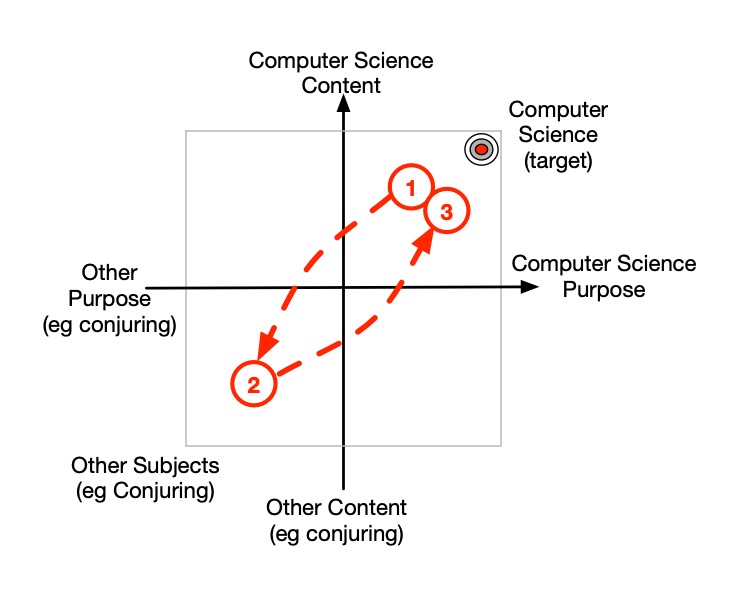

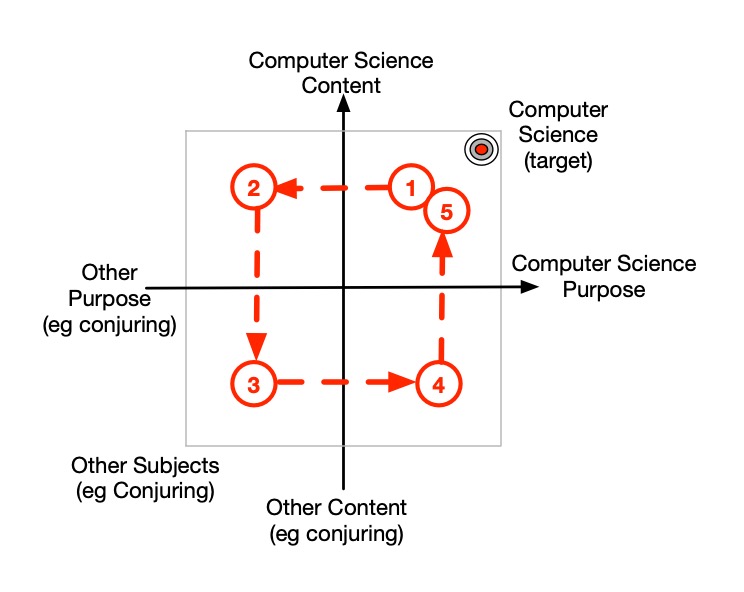

Suppose instead the plan is that we decide to improve the structure by adding a final step summarising the computer science again about what an algorithm is. The plan is then

- Explain what an algorithm is.

- Teach the Invisible Palming trick.

- Summarise what an algorithm is.

This can be visualised as in Figure 4 as a return trip. We may leave the target, but we return to it. We therefore do finish with a focus on Computer Science.

An autonomy tour

The return trip is better but still could be improved, making the linkage between tricks and algorithms clearer. An improved version may then be:

- Explain what an algorithm is.

- Teach the Invisible Palming trick.

- Explain how the trick is a self-working trick, and how that is equivalent to an algorithm (steps guaranteeing a result).

- Summarise what an algorithm is.

This can be visualised on the autonomy plane as in Figure 5. This is now an autonomy tour, moving between multiple quadrants. Step 3 is using the conjuring content from the trick that we now understand with a new purpose now. The purpose has moved from understanding the trick itself, to using our new understanding of conjuring and self-working tricks to understand what algorithms are. That is critically the way we solidly draw on understanding from other disciplines to better understand computer science. It is a quadrant where we strengthen linkages fromone discipline to another.

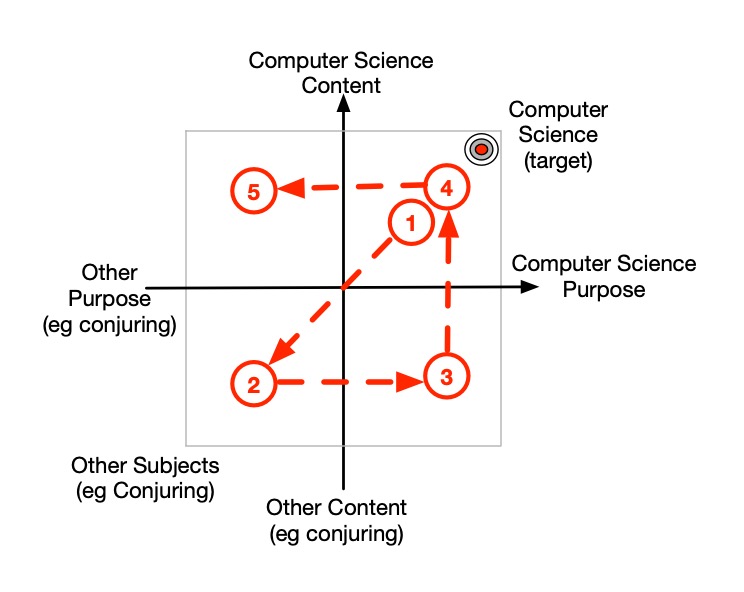

A longer autonomy tour

The final top-left quadrant is the use of computer science for the purpose of teaching other subjects. While our aim may ultimately be to teach computer science, applying the computer science we do know to the other subject can help increase understanding of both as we mutually strengthen the links in our heads. We could therefore build that quadrant into our tour too. With our conjuring-based lesson, after explaining what an algorithm is we use that to explain in general what a self-working trick is and how it allows a novice to do a trick without understanding how it works. We then actually do a trick to illustrate the idea explained.

- Explain what an algorithm is.

- Explain that some tricks are algorithmic in nature and guarantee a magical effect even with a novice who does not know why it works, just as a computer does not know what it is doing.

- Teach the Invisible Palming trick.

- Explain how the trick is a self-working trick, and how that is equivalent to an algorithm (steps guaranteeing a result).

- Summarise what an algorithm is.

This gives a full tour round all four quadrants as in Figure 6. That understanding would then be reinforced by then continuing the tour as above using the trick to cement the understanding of an algorithm.

A tour with an extension

The above plan however, loses something that we want when using conjuring: the initial grab of doing the trick without knowing why it works, creating a mystery to solve. We might therefore prefer not to do that. Instead, we might add a step on the end noting that magicians need some of the same computational thinking skills as computer scientists to invent new tricks that they can guarantee always work. Our new plan might then be:

- Explain what an algorithm is

- Teach the Invisible Palming trick

- Explain how the trick is a self-working trick, and how that is equivalent to an algorithm (steps guaranteeing a result).

- Summarise what an algorithm is.

- Explain how many tricks are algorithmic and that magicians have to use the same kind of computational thinking skills to invent tricks as programmers use when writing programs.

This does the shorter tour but then the final step is drawing on our knowledge of Computer Science to teach something about Conjuring and the thinking skills it uses. This might lead in to the next lesson (and a new autonomy tour) about those other skills needed such as evaluation skills.

Summary

There are many ways to teach a subject well and autonomy diagrams are not intended to be prescriptive of exactly how to do that. Rather, the autonomy plane diagram gives a quick and simple overview of the structure of a lesson. That allows us to think about whether that structure is appropriate given our aims, and if not suggests ways it might be improved. In general, round trips are better than one way trips or return trips. The precise order and quadrants visited, however may depend on the specific thing we are teaching. A tour could zig-zag around the plane, for example. What matters is the way we make use of the other non-target quadrants. The lower-right quadrant is perhaps most important as that is where we explicitly draw on the content of the other subjects to make links and so teach the target using that knowledge and understanding gained from other domains.

This post is based on a paper presented at LCT5:

Curzon, P. and Waite, J.Autonomy analysis of cross-curricular teaching: Turning LCT into pedagogy, Presented at LCT5, South Africa, January 2024. https://lctconferences.com/program/

For more on Autonomy in general see: https://legitimationcodetheory.com/theory/autonomy/